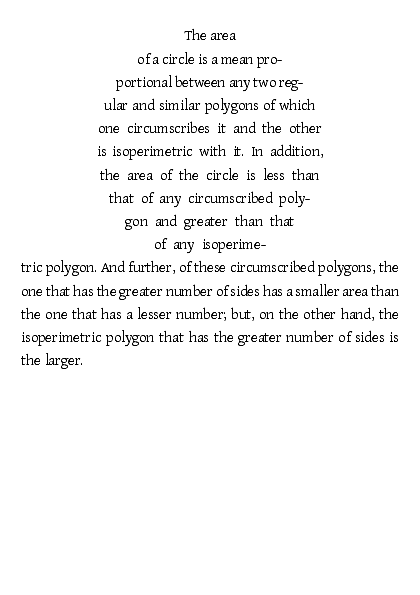

Basic typesetting (source) (PDF) |

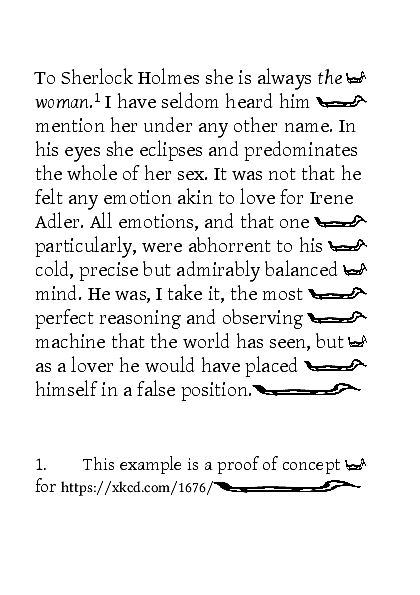

A Story (source) (PDF) |

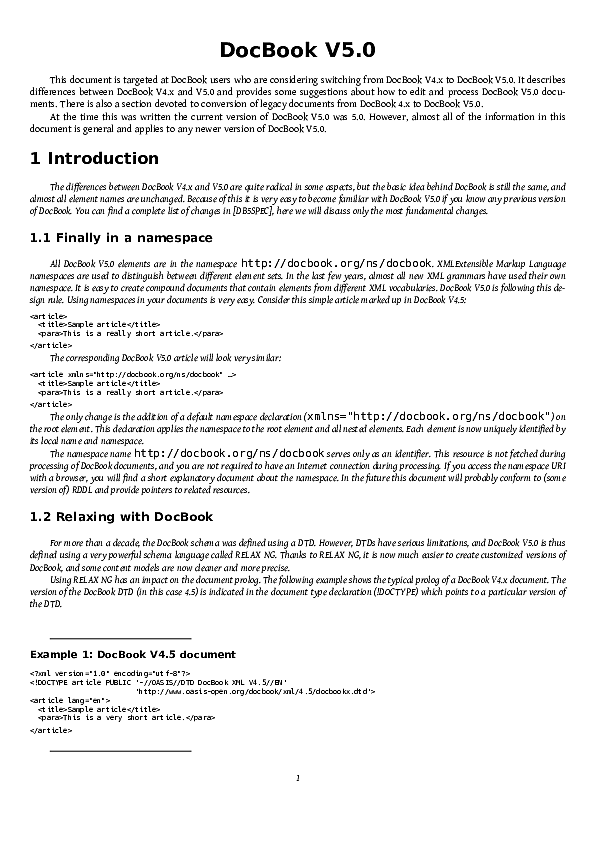

Docbook XML input (source) (PDF) |

Input filters (source) (PDF) |

Dynamically computed paragraph shapes (source) (PDF) |

Snake Justification (source) (PDF) |

SILE Examples

SIL Grammar

SILE accepts input in several formats. One is XML. Yes, just XML, no special input language required. Use any tooling you want to create XML. You can either target SILE's commands with XML tags or provide a module that handles the tag schema in your document.

Secondarily for those that want it, a custom intput syntax can be used that is somewhat less verbose and easier to type than XML.

We call it the SIL format (Sile Input Language).

Parsers

The current official reference parser is the Lua LPEG based EPNF variant found in inputters/sil-epnf.lua. Recently we've been working to define a formal grammar spec using ABNF syntax. The current version of this is distributed as sil.abnf along with SILE sources.

sil.abnf

; Formal grammar specification for SIL (SILE Input Language) files

;

; Uses RFC 5234 (Augmented BNF for Syntax Specifications: ABNF)

; Uses RFC 7405 (Case-Sensitive String Support in ABNF)

; IMPORTANT CAVEAT:

; Backus-Naur Form grammars (like ABNF and EBNF) do not have a way to

; express matching opening and closing tags. The grammar below does

; not express SILE's ability to skip over passthrough content until

; it hits the matching closing tag for environments.

; A master document can only have one top level content item, but we allow

; loading of fragments as well which can have any number of top level content

; items, hence valid grammar can be any number of content items.

document = *content

; Top level content can be any sequence of these things

content = environment

content =/ comment

content =/ text

content =/ braced-content

content =/ command

; Environments come in two flavors, passthrough (raw) and regular. The

; difference is what is allowed to terminate them and what escapes are needed

; for the content in the middle.

environment = %s"\begin" [ options ] "{" passthrough-command-id "}"

env-passthrough-text

%s"\end{" passthrough-command-id "}"

; ^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^^

; End command must match id used in begin, see caveat at top

environment =/ %s"\begin" [ options ] "{" command-id "}"

content

%s"\end{" command-id "}"

; ^^^^^^^^^^

; End command must match id used in begin, see caveat at top

; Passthrough (raw) environments can have any valid UTF-8 except the closing

; delimiter matching the opening, per the environment rule.

env-passthrough-text = *utf8-char

; Nothing to see here.

; But potentially important because it eats newlines!

comment = "%" *utf8-char CRLF

; Input strings that are not special

text = *text-char

; Input content wrapped in braces can be attached to a command or used to

; manually isolate chunks of content (e.g. to hinder ligatures).

braced-content = "{" content "}"

; As with environments, the content format may be passthrough (raw) or more SIL

; content depending on the command.

command = "\" passthrough-command-id [ options ] [ braced-passthrough-text ]

command =/ "\" command-id [ options ] [ braced-content ]

; Passthrough (raw) command text can have any valid UTF-8 except an unbalanced

; closing delimiter

braced-passthrough-text = "{"

*( braced-passthrough-text / braced-passthrough-char )

"}"

braced-passthrough-char = %x00-7A ; omit {

braced-passthrough-char =/ %x7C ; omit }

braced-passthrough-char =/ %x7E-7F ; end of utf8-1

braced-passthrough-char =/ utf8-2

braced-passthrough-char =/ utf8-3

braced-passthrough-char =/ utf8-4

options = "[" parameter *( "," parameter ) "]"

parameter = *WSP identifier *WSP "=" *WSP ( quoted-value / value ) *WSP

quoted-value = DQUOTE *quoted-value-char DQUOTE

quoted-value-char = "\" %x22

quoted-value-char =/ %x00-21 ; omit "

quoted-value-char =/ %x23-7F ; end of utf8-1

quoted-value-char =/ utf8-2

quoted-value-char =/ utf8-3

quoted-value-char =/ utf8-4

value = *value-char

value-char = %x00-21 ; omit "

value-char =/ %x23-2B ; omit ,

value-char =/ %x3C-5C ; omit ]

value-char =/ %x3E-7F ; end of utf8-1

value-char =/ utf8-2

value-char =/ utf8-3

value-char =/ utf8-4

text-char = "\" ( %x5C / %x25 / %x7B / %x7D )

text-char =/ %x00-24 ; omit %

text-char =/ %x26-5B ; omit \

text-char =/ %x5D-7A ; omit {

text-char =/ %x7C ; omit }

text-char =/ %x7E-7F ; end of utf8-1

text-char =/ utf8-2

text-char =/ utf8-3

text-char =/ utf8-4

letter = ALPHA / "_" / ":"

identifier = letter *( letter / DIGIT / "-" / "." )

passthrough-command-id = %s"ftl"

/ %s"lua"

/ %s"math"

/ %s"raw"

/ %s"script"

/ %s"sil"

/ %s"use"

/ %s"xml"

command-id = identifier

; ASCII isn't good enough for us.

utf8-char = utf8-1 / utf8-2 / utf8-3 / utf8-4

utf8-1 = %x00-7F

utf8-2 = %xC2-DF utf8-tail

utf8-3 = %xE0 %xA0-BF utf8-tail

/ %xE1-EC 2utf8-tail

/ %xED %x80-9F utf8-tail

/ %xEE-EF 2utf8-tail

utf8-4 = %xF0 %x90-BF 2utf8-tail

/ %xF1-F3 3utf8-tail

/ %xF4 %x80-8F 2utf8-tail

utf8-tail = %x80-BF

This grammar can be converted to a W3C EBNF grammar:

sil.ebnf

document ::= content*

content ::= environment

| comment

| text

| braced-content

| command

environment

::= '\begin' options? '{' passthrough-command-id '}' env-passthrough-text '\end{' passthrough-command-id '}'

| '\begin' options? '{' command-id '}' content '\end{' command-id '}'

env-passthrough-text

::= utf8-char*

comment ::= '%' utf8-char* CRLF

text ::= text-char*

braced-content

::= '{' content '}'

command ::= '\' passthrough-command-id options? braced-passthrough-text?

| '\' command-id options? braced-content?

braced-passthrough-text

::= '{' ( braced-passthrough-text | braced-passthrough-char )* '}'

braced-passthrough-char

::= [#x0-#x7A]

| '|'

| [#x7E-#x7F]

| utf8-2

| utf8-3

| utf8-4

options ::= '[' parameter ( ',' parameter )* ']'

parameter

::= WSP* identifier WSP* '=' WSP* ( quoted-value | value ) WSP*

quoted-value

::= DQUOTE quoted-value-char* DQUOTE

quoted-value-char

::= '\' '"'

| [#x0-#x21]

| [#x23-#x7F]

| utf8-2

| utf8-3

| utf8-4

value ::= value-char*

value-char

::= [#x0-#x21]

| [#x23-#x2B]

| [<-\]

| [#x3E-#x7F]

| utf8-2

| utf8-3

| utf8-4

text-char

::= '\' ( '\' | '%' | '{' | '}' )

| [#x0-#x24]

| [&-[]

| [#x5D-#x7A]

| '|'

| [#x7E-#x7F]

| utf8-2

| utf8-3

| utf8-4

letter ::= ALPHA

| '_'

| ':'

identifier

::= letter ( letter | DIGIT | '-' | '.' )*

passthrough-command-id

::= 'ftl'

| 'lua'

| 'math'

| 'raw'

| 'script'

| 'sil'

| 'use'

| 'xml'

command-id

::= identifier

utf8-char

::= utf8-1

| utf8-2

| utf8-3

| utf8-4

utf8-1 ::= [#x0-#x7F]

utf8-2 ::= [#xC2-#xDF] utf8-tail

utf8-3 ::= #xE0 [#xA0-#xBF] utf8-tail

| [#xE1-#xEC] utf8-tail utf8-tail

| #xED [#x80-#x9F] utf8-tail

| [#xEE-#xEF] utf8-tail utf8-tail

utf8-4 ::= #xF0 [#x90-#xBF] utf8-tail utf8-tail

| [#xF1-#xF3] utf8-tail utf8-tail utf8-tail

| #xF4 [#x80-#x8F] utf8-tail utf8-tail

utf8-tail

::= [#x80-#xBF]

Railroad digrams and EBNF snippets

What followes is EBNF grammar snippets and railroad diagrams for the syntax.

document:

document ::= content*

content:

content ::= environment

| comment

| text

| braced-content

| command

referenced by:

- braced-content

- document

- environment

environment:

environment

::= '\begin' options? '{' passthrough-command-id '}' env-passthrough-text '\end{' passthrough-command-id '}'

| '\begin' options? '{' command-id '}' content '\end{' command-id '}'

referenced by:

- content

env-passthrough-text:

env-passthrough-text

::= utf8-char*

referenced by:

- environment

comment:

comment ::= '%' utf8-char* CRLF

referenced by:

- content

text:

text ::= text-char*

referenced by:

- content

braced-content:

braced-content

::= '{' content '}'

referenced by:

- command

- content

command:

command ::= '\' passthrough-command-id options? braced-passthrough-text?

| '\' command-id options? braced-content?

referenced by:

- content

braced-passthrough-text:

braced-passthrough-text

::= '{' ( braced-passthrough-text | braced-passthrough-char )* '}'

referenced by:

- braced-passthrough-text

- command

braced-passthrough-char:

braced-passthrough-char

::= [#x0-#x7A]

| '|'

| [#x7E-#x7F]

| utf8-2

| utf8-3

| utf8-4

referenced by:

- braced-passthrough-text

options:

options ::= '[' parameter ( ',' parameter )* ']'

referenced by:

- command

- environment

parameter:

parameter

::= WSP* identifier WSP* '=' WSP* ( quoted-value | value ) WSP*

referenced by:

- options

quoted-value:

quoted-value

::= DQUOTE quoted-value-char* DQUOTE

referenced by:

- parameter

quoted-value-char:

quoted-value-char

::= '\' '"'

| [#x0-#x21]

| [#x23-#x7F]

| utf8-2

| utf8-3

| utf8-4

referenced by:

- quoted-value

value:

value ::= value-char*

referenced by:

- parameter

value-char:

value-char

::= [#x0-#x21]

| [#x23-#x2B]

| [<-\]

| [#x3E-#x7F]

| utf8-2

| utf8-3

| utf8-4

referenced by:

- value

text-char:

text-char

::= '\' ( '\' | '%' | '{' | '}' )

| [#x0-#x24]

| [&-[]

| [#x5D-#x7A]

| '|'

| [#x7E-#x7F]

| utf8-2

| utf8-3

| utf8-4

referenced by:

- text

letter:

letter ::= ALPHA

| '_'

| ':'

referenced by:

- identifier

identifier:

identifier

::= letter ( letter | DIGIT | '-' | '.' )*

referenced by:

- command-id

- parameter

passthrough-command-id:

passthrough-command-id

::= 'ftl'

| 'lua'

| 'math'

| 'raw'

| 'script'

| 'sil'

| 'use'

| 'xml'

referenced by:

- command

- environment

command-id:

command-id

::= identifier

referenced by:

- command

- environment

utf8-char:

utf8-char

::= utf8-1

| utf8-2

| utf8-3

| utf8-4

referenced by:

- comment

- env-passthrough-text

utf8-1:

utf8-1 ::= [#x0-#x7F]

referenced by:

- utf8-char

utf8-2:

utf8-2 ::= [#xC2-#xDF] utf8-tail

referenced by:

- braced-passthrough-char

- quoted-value-char

- text-char

- utf8-char

- value-char

utf8-3:

utf8-3 ::= #xE0 [#xA0-#xBF] utf8-tail

| [#xE1-#xEC] utf8-tail utf8-tail

| #xED [#x80-#x9F] utf8-tail

| [#xEE-#xEF] utf8-tail utf8-tail

referenced by:

- braced-passthrough-char

- quoted-value-char

- text-char

- utf8-char

- value-char

utf8-4:

utf8-4 ::= #xF0 [#x90-#xBF] utf8-tail utf8-tail

| [#xF1-#xF3] utf8-tail utf8-tail utf8-tail

| #xF4 [#x80-#x8F] utf8-tail utf8-tail

referenced by:

- braced-passthrough-char

- quoted-value-char

- text-char

- utf8-char

- value-char

utf8-tail:

utf8-tail

::= [#x80-#xBF]

referenced by:

- utf8-2

- utf8-3

- utf8-4

What is SILE?

SILE is a typesetting system. Its job is to produce beautiful printed documents. The best way to understand what SILE is and what it does is to compare it to other systems which you may have heard of.

SILE versus Word

When most people produce printed documents using a computer, they usually use software such as Word (part of Microsoft Office) or Writer (part of Open/LibreOffice) or similar–word processing software. SILE is not a word processor; it is a typesetting system. There are several important differences.

The job of a word processor is to produce a document that looks exactly like what you type on the screen. SILE takes what you type and considers it instructions for producing a document that looks as good as possible.

For instance, in a word processor, you keep typing and when you hit the right margin, your cursor will move to the next line. It is showing you where the lines will break. SILE doesn’t show you where the lines will break, because it doesn’t know yet. You can type and type and type as long a line as you like, and when SILE comes to process your instructions, it will consider your input (up to) three times over in order to work out how to best to break the lines to form a paragraph. Did we end two successive lines with a hyphenated word? Go back and try again.

Similarly for page breaks. When you type into a word processor, at some point you will spill over onto a new page. In SILE, you keep typing, because the page breaks are determined after considering the layout of the whole document.

Word processors often describe themselves as WYSIWYG–What You See Is What You Get. SILE is cheerfully not WYSIWYG. In fact, you don’t see what you get until you get it. Rather, SILE documents are prepared initially in a text editor–a piece of software which focuses on the text itself and not what it looks like–and then ran through SILE in order to produce a PDF document.

In other words, SILE is a language for describing what you want to happen, and SILE will make certain formatting decisions about the best way for those instructions to be turned into print.

SILE versus TeX

Ah, some people will say, that sounds very much like TeX. If you don’t know much about TeX or don’t care, you can probably skip this section.

But it’s true. SILE owes an awful lot of its heritage to TeX. It would be terribly immodest to claim that a little project like SILE was a worthy successor to the ancient and venerable creation of the Professor of the Art of Computer Programming, but… really, SILE is basically a modern rewrite of TeX.

TeX was one of the earliest typesetting systems, and had to make a lot of design decisions somewhat in a vacuum. Some of those design decisions have stood the test of time–and TeX is still an extremely well-used typesetting system more than thirty years after its inception, which is a testament to its design and performance–but many others have not. In fact, most of the development of TeX since Knuth’s era has involved removing his early decisions and replacing them with technologies which have become the industry standard: we use TrueType fonts, not METAFONTs (xetex); PDFs, not DVIs (pstex, pdftex); Unicode, not 7-bit ASCII (xetex again); markup languages and embedded programming languages, not macro languages (xmltex, luatex). At this point, the parts of TeX that people actually use are 1) the box-and-glue model, 2) the hyphenation algorithm, and 3) the line-breaking algorithm.

SILE follows TeX in each of these three areas; it contains a slavish port of the TeX line-breaking algorithm which has been tested to produce exactly the same output as TeX given equivalent input. But as SILE is itself written in an interpreted language, it is very easy to extend or alter the behaviour of the SILE typesetter.

For instance, one of the things that TeX can’t do particularly well is typesetting on a grid. This is something that people typesetting bibles really need to have. There are various hacks to try to make it happen, but they’re all horrible. In SILE, you can alter the behaviour of the typesetter and write a very short add-on package to enable grid typesetting.

Of course, nobody uses plain TeX–they all use LaTeX equivalents plus a huge repository of packages available from the CTAN. SILE does not benefit from the large ecosystem and community that has grown up around TeX; in that sense, TeX will remain streets ahead of SILE for some time to come. But in terms of capabilities, SILE is already certainly equivalent to, if not somewhat more advanced than, TeX.

SILE versus InDesign

The other tool that people reach for when designing printed material on a computer is InDesign.

InDesign is a complex, expensive, commercial publishing tool. It’s highly graphical–you click and drag to move areas of text and images around the screen. SILE is a free, open source typesetting tool which is entirely text-based; you enter commands in a separate editing tool, save those commands into a file, and hand it to SILE for typesetting. And yet the two systems do have a number of common features.

In InDesign, text is flowed into frames on the page. SILE also uses the concept of frames to determine where text should appear on the page, and so it’s possible to use SILE to generate page layouts which are more flexible and more complex than that afforded by TeX.

Another thing which people use InDesign for is to turn structured data in XML format–catalogues, directories and the like–into print. The way you do this in InDesign is to declare what styling should apply to each XML element, and as the data is read in, InDesign formats the content according to the rules that you have declared.

You can do exactly the same thing in SILE, except you have a lot more control over how the XML elements get styled, because you can run any SILE command you like for a given element, including calling out to Lua code to style a piece of XML. Since SILE is a command-line filter, armed with appropriate styling instructions you can go from an XML file to a PDF in one shot. Which is quite nice.

In the final chapters of this book, we’ll look at some extended examples of creating a class file for styling a complex XML document into a PDF with SILE.

Conclusion

SILE takes some textual instructions and turns them into PDF output. It has features inspired by TeX and InDesign, but seeks to be more flexible, extensible and programmable than them. It’s useful both for typesetting documents such as this one written in the SILE language, and as a processing system for styling and outputting structured data.